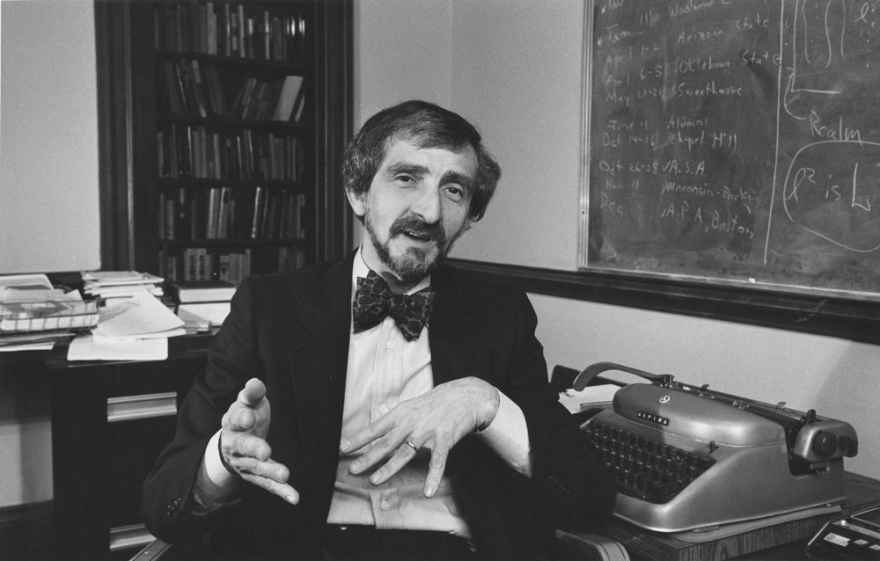

Ted Cohen, Philosopher Who Found the Extraordinary in the Ordinary, 1939–2014

The following obituary was published on March 18 by the UChicago News Office. Two additional obituaries have subsequently been published by the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Sun-Times.

A memorial service will be held at 5 p.m. on April 12 at the Quadrangle Club, 1155 E. 57th Street. The Department of Philosophy created an online guest book for those who knew Ted Cohen to leave a remembrance.

Ted Cohen, a philosopher whose agile intellect and wry humor made him a UChicago campus legend, died Friday after a brief hospitalization. He was 74.

Over a career that spanned more than 50 years, Cohen, professor in philosophy and the College, turned his eye to a vast range of subjects that included jokes, baseball, television, photography, painting and sculpture, as well as the philosophy of language and formal logic.

“He was proud of bringing philosophy to everything he looked at,” said his daughter Shoshanna Cohen.

While some philosophers aim to construct large-scale theories, others “look with a very fine, acute eye at specific phenomena and work from the example outwards, beginning with the ordinary and exposing the extraordinary within it,” said Cohen’s longtime friend and colleague Josef Stern. “Ted was that kind of philosopher.”

Endlessly curious, “if he was working on Velasquez one day, he could be working on metaphor the next,” said fellow friend and collaborator Joel Snyder, professor in art history and the College.

TAKING HUMOR SERIOUSLY

Many remember Cohen, AB’62, for his legendary wit. But humor was more than a hallmark of his personality—it was also the subject of some of Cohen’s major contributions to his field.

Indeed, “he’s one of the first philosophers who took jokes seriously,” said Stern, the William H. Colvin Professor of Philosophy and director of the Chicago Center for Jewish Studies.

Cohen’s 1999 book, Jokes: Philosophical Thoughts on Joking Matters, offered a lively and accessible take on how and why jokes work.

Liberally sprinkled with some of Cohen’s favorite groaners (“What do Alexander the Great and Winnie the Pooh have in common? They have the same middle name”), Jokes examines the role of humor in creating intimacy and a sense of community.

“I need reassurance that this something inside of me, the something that is tickled by a joke, is indeed something that constitutes an element of my humanity,” he wrote. “I discover something of what it is to be a human being by finding this thing in me, and then having it echoed in you, another human being.

“Of course I want you to like the one about Winnie the Pooh…But I also need you to like it, because in your liking I receive a confirmation of my own liking.”

In addition to his work on humor, Cohen also made major contributions to the study of metaphor. His 2008 book Thinking of Others: On the Talent for Metaphor synthesized his years of work on the topic, arguing that the ability to think of one thing as another is an essential human capacity that makes sound moral judgment possible.

PHILOSOPHER, WRITER, TEACHER

Cohen was widely praised for his elegant, precise and engaging writing style. He won the Pushcart Prize—a literary honor—in 1991 for his essay “There are No Ties at First Base.”

“He was as much a writer as he was a philosopher,” said his wife Andy Austin Cohen.

Cohen was the president of the American Philosophical Association from 2006-2007 and the American Society for Aesthetics from 1997-1998, among many other professional honors. He chaired the Department of Philosophy from 1974-1979.

He was also a dedicated teacher who won the Llewellyn John and Harriet Manchester Quantrell Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching in 1983.

Amy Chou, AB’12, remembered Cohen as “a vibrant presence” in the classroom who was as quick to tell a story as he was to lavish praise on the work of his colleagues. Chou remembered arriving to class early in hopes of chatting with Cohen as he smoked on the steps of Harper. “I would always emerge from those conversations covered in ash,” she recalled. “But it was totally worth it.”

Cohen also made his mark as the longtime moderator of the University’s famed Latke-Hamantash Debate—though not an impartial one. “The hamantash is a very, very good thing of its kind,” he argued in the 1976 debate. “The latke, however, is a perfect thing. Now that I’ve laid the conclusion out, perhaps its transparent correctness is already evident to you.”

He was also a longtime participant in the Revels, the faculty-produced satirical revue.

In his leisure time, Cohen enjoyed playing pool at the Quadrangle Club, where in recent years he enjoyed a weekly lunch with his daughter Shoshannah, who works in the Office of the University Registrar.

The avid White Sox fan was also a talented jazz drummer and piano player who enjoyed music of all kinds. He loved movies and kept a cardboard cutout of John Wayne in the entryway to his Hyde Park home.

Cohen was raised in the small farming community of Hume, Ill. He holds a bachelor’s degree from UChicago and a PhD from Harvard University, where he studied under the legendary philosopher Stanley Cavell.

Cohen is survived by his wife Andy Austin Cohen, his son Amos Cohen and grandson Asher Cohen, his daughter Shoshannah Cohen and son-in-law Elmer Almachar, his brother Stephen Cohen, and his aunt, Peg Kay.

The family will sit shiva on Friday, March 21 from 4 p.m. to sundown at Cohen’s home in Hyde Park. A memorial service will be held April 12 at the Quadrangle Club. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the American Civil Liberties Union.