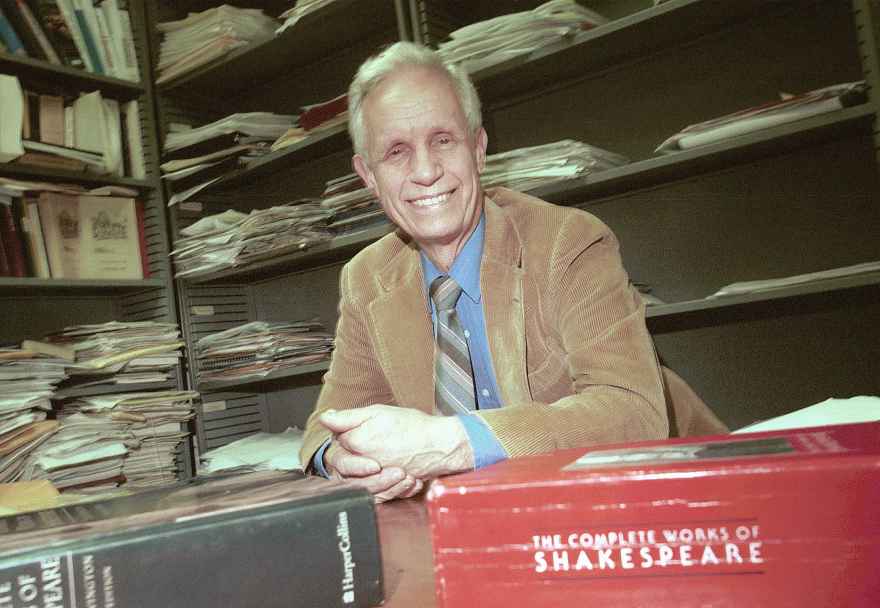

David Bevington, Preeminent Shakespeare Scholar, 1931-2019

The following was published by UChicago News on August 5, 2019.

By Sara Patterson

Prof. Emeritus David Bevington, the extraordinarily prolific editor of Shakespeare’s full canon and author of seminal books about English Renaissance playwrights, died peacefully at home in Chicago on Aug. 2. He was 88 years old.

Remembered by friends and family as a vibrant, generous and intellectually inquisitive man, the longtime University of Chicago professor possessed an infectious enthusiasm for the works he taught. He lived life with boundless energy—teaching, writing, hosting social events and playing chamber music with friends until just before he died.

As a scholar, Bevington helped build UChicago’s Department of English Language and Literature into a national center for graduate study in the English Renaissance.

“David was a great editor of Shakespeare’s plays both for scholars and for more general audiences,” said Prof. Emeritus Richard Strier. “He had infinite patience and sweated out the details of language and punctuation, writing careful notes to clarify knotty texts for readers.”

Prof. Joshua Scodel praised Bevington’s “combination of historical erudition, deep engagement with Renaissance stagecraft, and profound insights into the human condition.” He cited three of Bevington’s many books: From “Mankind” to Marlowe (1962), a classic study of the transition from Medieval to Renaissance Drama; Tudor Drama and Politics (1968) a pioneering analysis of the historical topicality of Tudor plays; and Action Is Eloquence (1984), a wide-ranging treatment of gesture and the visual aspects of Shakespearean drama.

“David bridged the gap between the historicist analysis of Shakespeare and the critical appreciation of his abiding relevance to contemporary audiences,” Scodel said.

Bevington also helped edit The Cambridge Edition of The Works of Ben Jonson, collaborating on the massive undertaking with Martin Butler (University of Leeds) and Ian Donaldson (University of Melbourne). Collecting the complete works of the English playwright, the volumes were printed in 2012 and are also available in digital form, unusual at the time for such a large body of literary text.

Bevington made an impact as a medievalist as well—publishing Medieval Drama, a singular collection of medieval dramatic texts, in 1975. He prepared a second edition, published in 2012.

Bevington championed the value of teaching at all levels of higher education. A 1979 winner of the Quantrell Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, he also taught continuing education classes at the University of Chicago Graham School as recently as 2018.

One of Bevington’s first graduate students at UChicago was David Kastan, now an English professor at Yale. When Kastan, PhD’75, was on the verge of dropping out of his doctoral program and re-applying to law school, it was Bevington who convinced him to stay.

“Taking his course and getting to know David changed my life forever,” Kastan said. “I have never met anyone so instinctively generous.

“David gave my generation and subsequent generations of students the confidence to add to the 400-year conversation about Shakespeare and other English Renaissance playwrights. He gave us the plausible encouragement to believe that what we did mattered and gave us a wonderful sense that we are in this together.”

Bevington was born in New York City in 1931. At 11 and 9 years old, respectively, he and younger brother Philip moved to Durham, North Carolina, where their father Merle Bevington became a professor of Victorian Studies at Duke University. Their mother Helen Smith Bevington, PhB’26, also joined the English department at Duke, and was an accomplished light verse writer who later penned the acclaimed memoir Charley Smith’s Girl.

David Bevington graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in 1948. He then attended Harvard University, majoring in History and Literature and enrolling in the Navy ROTC program. He obtained his undergraduate degree in 1952, and served three years as a junior officer on a destroyer. That Bevington was able to fund his education through his service left him feeling indebted to society at large—a privilege he was always conscious to repay.

Bevington returned to Harvard after his naval service, earning a PhD in 1957 and teaching from 1959-61. He then taught for six years at the University of Virginia, where he collaborated frequently with bibliographer Fredson Bowers, who headed UVA’s English department and also held a stint as a UChicago visting professor. Bevington was promoted from assistant professor to associate professor in 1964, and to professor in 1966.

He accepted a visiting position at UChicago in 1967, which morphed into a full-time faculty appointment the following year. In 1985, Bevington was named the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities.

“We love Virginia, but Chicago had such a revered name,” he said in a 2016 interview. “We felt very much at home from the word ‘go.’ It was a tight intellectual community. … Why leave the University of Chicago when you could be here? The question sort of answers itself, really, why one wants to stay.”

In addition to his work as a scholar of English literature—which earned him Guggenheim Fellowships in 1964 and 1981—Bevington helped UChicago establish Theater and Performance Studies as a major in the undergraduate College. He also led frequent post-performance discussions at Court Theatre.

David is survived by Peggy, his wife of 66 years; his children Stephen, Kate and Sarah; and by his five grandchildren, Sylvia, Zeke, Peter, Leo and Maggie. He was preceded in death by his son Philip, who died in 1977; and his brother Philip, a physicist who died in 1979.