Humanities Day Keynote to Examine How Home Movies Represent Cultural History

The following was published in UChicago News on October 10, 2019.

By Sara Patterson

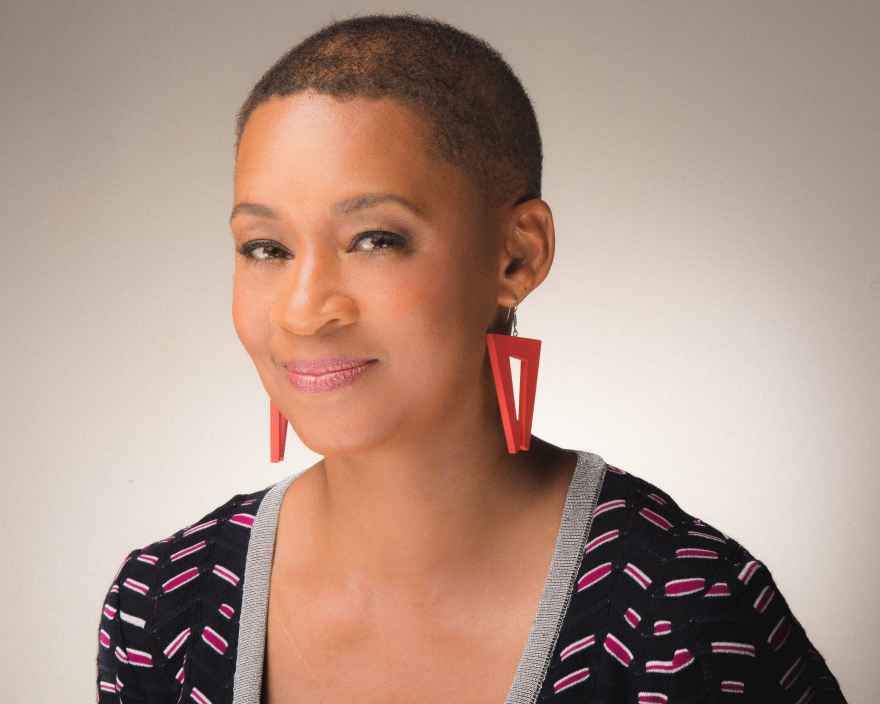

For more than a decade, Prof. Jacqueline Najuma Stewart has worked to preserve, digitize and exhibit an understudied cultural resource: home movies from the Chicago neighborhoods in which she was born and raised.

In addition to founding the South Side Home Movie Project in 2005, the renowned University of Chicago scholar has earned national acclaim for her research on silent films—and was recently selected as Turner Classic Movies’ first scholar and African American host.

On Oct. 19, Stewart will discuss what home movie archives can teach us during her keynote address at Humanities Day, a daylong series of 40 on-campus events celebrating the research of the UChicago intellectual community. Her talk, which begins at 11 a.m. in Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago, coincides with Home Movie Day, an international effort to preserve amateur films.

Stewart, who teaches in the Department of Cinema and Media Studies, recently spoke about the motivations behind her work and what she hopes to accomplish with TCM. Below is an edited version of that conversation.

How did you become interested in exploring and advocating for mid-century home movies of South Side Chicagoans?

I was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago. I have always felt that narratives about Chicago did not take into account the everyday life and community experiences of people living on the South Side. The news media focuses on violence and crime in ways that do not resonate with my experience. When I began asking people if they had home movies, it became clear that this practice of informal representation could give us a deeper understanding of the rich cultural histories of South Side neighborhoods.

As a film historian, I became interested in orphan films, works that exist outside of commercial filmmaking. While commercial, narrative films have dominated the study of film, a growing number of scholars have been looking at orphan films like those for training, education, scientific inquiry and advertising. Home movies are an important part of this underexplored area of nontheatrical media. Traditionally, institutions have not archived amateur films. I became intrigued to learn what these home movies tell us about the histories of filmmaking as well as the histories of the communities they come from.

Why is it important to study these home movies?

Home movies show us how everyday people use cameras to record their lives. They represent an important creative practice in themselves, and they capture other creative practices–like fashion, cooking, home décor, private and public performance. We can also think about how home movies relate to our current selfie culture, and the dynamic role that the camera continues to play in our everyday lives. We take so many photos and videos with our phones, many more than we can ever go through. And as groups, we record the same things, often at the same time: the same concert or monument. There’s something valuable about the act of recording images beyond creating a keepsake that we will engage with later. I am curious to understand more about the motivations behind personal moviemaking, and about the place of home movies in the long history of personal documentation.

How has your interest grown to encompass the preservation of amateur films?

During my recent research on amateur films in the collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, I learned more about the possibilities that emerge through home movie digitization. The museum has a community-engaged "Great Migration" project that evokes two great migrations—the historical movement of African Americans from south to points north and west, and the migration of data from analog to digital formats. Watching people bring their materials into the museum for digitization enabled them to see the connection between their personal movies and the grand narrative of African American experience that the museum presents throughout that spectacular building. As I look to the next phases of the South Side Home Movie Project, I plan to develop a space here to do similar work on a regular basis. As Director of the University's Arts + Public Life initiative, I want to work with members of the Washington Park community in particular to preserve their films and videos, their artifacts and stories, so that they can be seen and shared with neighbors, artists, scholars and students.

What do you hope to accomplish as the host of ‘Silent Movie Sundays’ at TCM?

I am the first TCM host who conducts scholarly research. I am looking forward to bringing my insights as a scholar to my film introductions, and sharing more information on the network's online platforms. TCM has developed a tightknit community, where viewers share a passion for knowledge of movies with the hosts and with each other. It is just as exciting to learn from this audience as it is to bring new information to them.

In many ways, my role at TCM is an extension of the film exhibition projects I've been doing on and off campus since I was a graduate student at UChicago. Many years ago, I curated a series on early African American cinema at Doc Films that included Oscar Micheaux's Body and Soul (1925) with live musical accompaniment. This is Paul Robson's first film, and when we screened it, hundreds of people lined up around the block to get in. I have hosted many film screenings on campus, and I think it is important to share the rich resources we have for film presentation with South Siders. We have the capacity to screen film prints, for example, which is becoming increasingly rare. My current film series is Cinema 53 at the Harper Theater, a free monthly program presenting works by and about women and people of color. Like Silent Movie Sundays, this program seeks to share works that are otherwise difficult to see, and we always featuring post-screening discussion, where audiences can dialogue with filmmakers, other artists, scholars, activists and youth.

What can we learn today by watching silent movies?

Silent movies are incredibly diverse in styles and origins. In the span of 30 years, silent films developed from a kind of fairground display to a sophisticated mode of storytelling, including the adaptation of literary and theatrical works as well as the crafting of original stories in cinematic language. Filmmakers drew from many creative sources across this period of experimentation, and developed not only the recording technologies of cinema, but also strategies to create coherent stories, spatial continuity and convincing character psychology. Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), for example, is a masterpiece of silent cinema for the riveting ways in which it uses close-ups to capture Joan's subtle emotional states, as conveyed by actress Maria Falconetti. When we look at silent films, we can see the origins of filmmaking techniques that became commonplace, as well as the unique and striking aspects of cinematic representation without synchronized sound. These films show how pioneering artists around the world developed the 20th century's most popular and influential medium.