From Concerts to Museums, UChicago Artists Find New Inspiration Under Quarantine

The following was published in UChicago News on May 29, 2020.

By Jack Wang

What does a pandemic mean for the arts?

The COVID-19 crisis has forced the widespread closures of theaters, concert halls and other cultural institutions, across the United States and beyond. Even the venues that manage to survive a prolonged shutdown might reemerge in a very different world—one that could dramatically reshape interactions between performers and audiences.

Some University of Chicago scholars and artists are already adapting to this reality. From soaring orchestra compositions to intimate home movie livestreams, these projects explore the arts in new ways, connecting to the public at a time when many are feeling increasingly isolated.

Composing for hope

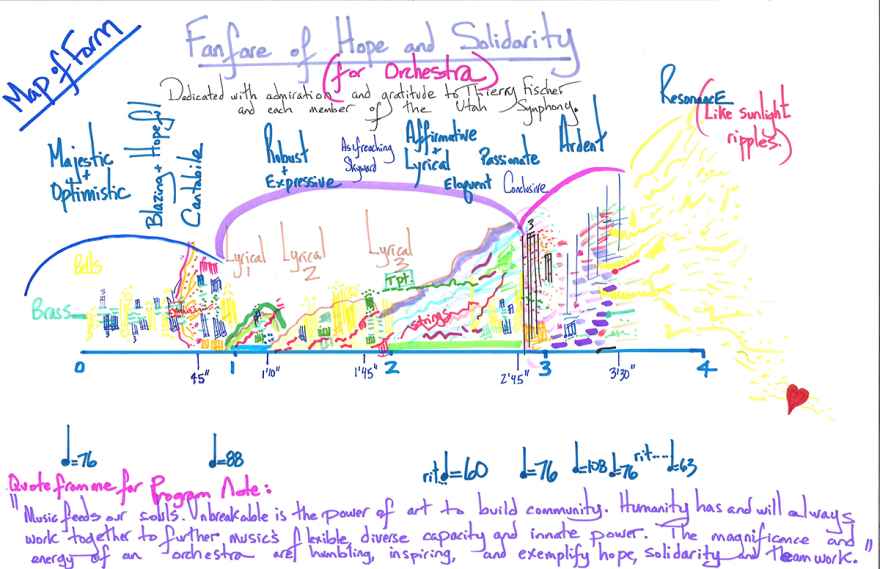

Prof. Augusta Read Thomas has composed for symphonies all over the world, winning acclaim for her distinctive artistic voice. Now, she has written something tailored for a virtual performance, played by musicians quarantined in their respective homes.

Titled “Fanfare of Hope and Solidarity,” the four-minute piece was the result of a request from Utah Symphony director Thierry Fischer. Working from his home in Switzerland, Fischer asked for something that would sound cohesive without a shared physical space—but would also work once his orchestra can reconvene on stage.

Thomas completed it in just two weeks.

“I have to tailor the piece for what the project is,” she said. “That’s been kind of fun in a way. ‘Here are a lot of limitations. Now, make a piece of art.’”

The Utah Symphony premiered "Fanfare of Hope and Solidarity" on May 22, with each musician playing from their respective homes.

One consideration was percussion. Large percussion set-ups are characteristic of many of Thomas’ orchestral works, but because those were not available, she wrote for whatever happened to be in basements or garages—a triangle, a bell. She also opted for more solos and avoided interpretive notations like fermatas, pauses held at the discretion of the conductor. “You have to write something that makes people sound good, even though they’re sitting at home and playing alone out of the context of all the other orchestral colors and meanings,” she said.

An optimist, Thomas still believes that live concerts will eventually return, even if those performances might require smaller audiences or other protective measures. The great works of Bach, Mozart and other composers have survived hundreds of years, she said, and there are too many talented musicians today itching to play them.

So, she keeps working.

“In a way, composers are fortunate,” Thomas said. “What we mostly need is time. And here it comes on a silver platter.”

Remembering museums

Rachel Cohen has kept a museum notebook on and off for nearly a decade, writing about photos she has taken of paintings, statues and other artworks. The project has been mostly personal—a way for her to reflect, to find details she may have missed in the moment.

But what happens when those museums are closed?

“It becomes a little portal into this world of memory and imagination that’s inaccessible in person right now,” said Cohen, a professor of practice in the arts in the Department of English Language and Literature and the Program in Creative Writing.

Since shelter-in-place policies began in March, Cohen has reoriented the project as a sort of “remembered museum,” writing six times a week with a more public audience in mind. She named it The Frederick Project, a nod to a children’s book by Leo Lionni about a mouse (Frederick) who studies colors in the summer, and tells other mice what he remembers in the winter.

How Cohen chooses her topic varies. Sometimes, her imagination is sparked by colors she sees—the green arriving on trees, the emotions evoked by the color blue. Other days, she wakes up with a certain image in mind, or an occasion she wants to commemorate.

The notebook found a larger audience in late April, when Cohen published an essay about it in The New Yorker. She had already shared the project with colleagues and students, but the essay sparked a flurry of responses from strangers. One e-mail came from a Chicago Public Schools art teacher, who wrote that he had been moved to tears.

“It was a surprisingly deep connection from someone I don’t know,” Cohen said. “I think that’s a sign of the release people have needed.”

Recreating the stage

Even with its stage dark, Court Theatre has found ways to connect with audiences and performers. Earlier this month, it began the first round of its Virtual Monologue Fest, a workshop series that pairs participants with professional artists.

Serving on a small team of Court staff organizers, actor Michael Aaron Pogue designed the sessions to give undergraduates a chance to develop their writing and acting skills —working on monologues from recent productions of King Hedley II and Oedipus Rex, as well as original writing.

Being able to see, hear and speak to others has helped sustain some of the connective possibilities of theater. Although the workshops aren’t held in a shared physical space, they still offer similar opportunities for creative growth.

“It’s been thrilling to feel that energy,” said Pogue, a Court Theatre education associate and teaching artist. “It gives me a lift moving forward with my day.”

Being able to see, hear and speak to others has helped sustain some of the connective possibilities of theater.

Produced in conjunction with the Office of Civic Engagement, Court also hopes to open future rounds of the free series to other members of the UChicago community, as well as Chicago Public Schools students and local residents. No acting or writing experience is required, and past participants are welcome to register again.

“Our workshop is structured to respond to what participants resonate with, as opposed to an assignment testing their aptitude,” Pogue said. “Professional artists are in dialogue with students, hearing their stories as we all connect with each other during quarantine from home.”

Home movies, remixed

From backyard barbecues to family vacations, home movies provide a uniquely intimate view into the lives of ordinary people. Those are the sorts of moments collected and preserved by the South Side Home Movie Project, founded in 2005 by UChicago film scholar Jacqueline Stewart.

For the past two months, that archive has found a different format: weekly DJ sessions.

Earlier this spring, the SSHMP invited eight local DJs to dive into its home movie archive and create one-of-a-kind soundtracks for selected films. Every Thursday night, “Spinning Home Movies” livestreamed these unique audio/visual programs—along with interviews with the DJs and film donors—and invited at-home viewers to reminiscence in the comments. The new series builds on the SSHMP’s history of artistic collaboration and public programming, including a 2018 multimedia performance with poet and singer Jamila Woods.

More than 6,000 people have watched “Spinning Home Movies” so far, with nearly a third tuning in from outside Illinois.

“These films are really precious documents of everyday life on the South Side of Chicago,” said Stewart, a professor in the Department of Cinema and Media Studies. “We thought that while we’re all sheltering in place, this would be a really great moment to reflect on and celebrate this amateur footage.”

A co-production of the SSHMP and UChicago’s Arts + Public Life initiative, “Spinning Home Movies” wrapped up its initial eight-episode run in May. It will start again in mid-June, hosting musicians and visual artists along with DJs.