The Hidden History of 'Guerrilla Television': UChicago Scholars Preserve Decades-Old Videos

The following was published in UChicago News on May 25, 2021.

By Sara Patterson

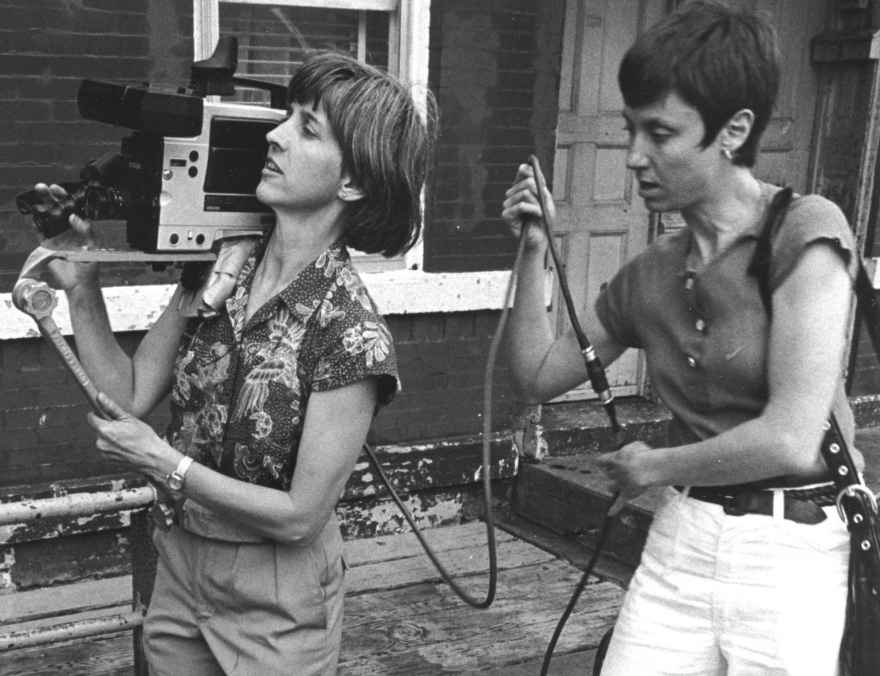

Decades before cellphone video changed how we create and consume media, the advent of low-cost, portable video cameras did something similar for underrepresented communities across the United States—allowing them to experiment with new forms of documentary, art and activism.

Known as “guerrilla television,” this movement of the late 1960s to 1970s helped amplify the voices of groups such as women, Black, Indigenous and people of color, immigrants and Appalachian miners.

Now, a consortium of University of Chicago scholars, librarians, and partnering archivists and filmmakers will create the Guerrilla Television Network—preserving and presenting the history of guerrilla television to a much wider audience. Supported by a grant of nearly $500,000 from the Council on Library and Information Resources, the three-year project will digitize 1,015 videotapes produced from 1967 to 1979.

“When Sony rolled out the small format video in the 1960s, this revolutionary equipment placed TV in the hands of everyday people,” said longtime filmmaker Judy Hoffman, a professor of practice in the arts in UChicago’s Department of Cinema and Media Studies. “The technology intersected at a time of cultural upheaval when people questioned how broadcast TV was produced. Those of us interested in changing our relationship to TV got hold of this equipment.”

These videos, she added, didn’t just observe people, but rather created a participatory media about the lives and concerns of those who are too often overlooked: “The guerrilla television movement videos represent something that is not taught, is not available to most people and creates a new wealth of cultural knowledge.”

Coined by early video author Michael Shamberg, who later became a Hollywood movie producer, the term “guerilla television” describes a movement that sought to democratize video production—blurring the lines between those who had the power to disseminate information and who could only receive it. The new preservation effort will draw from videotapes held in the collections six media arts organizations: Media Burn, Community TV Network, Kartemquin, Appalshop, NOVAC and the Experimental Television Center collection at Cornell University.

Through the process of digitization and extensive cataloging, the consortium will create a permanent online archive accessible to the public.

“Most of these films haven’t been seen since the time when they were made,” said Prof. Daniel Morgan, chair of the Department of Cinema and Media Studies. “To gain access to this material will give us a broader sense of media history, especially the intersection of technology and politics. It promises to change how we think about media during the 1970s.”

Media Burn chair and founder Tom Weinberg called the project a “technological breakthrough that has artistic and cultural significance.” Media Burn executive director Sara Chapman, AB’04, who studied with Hoffman, said the new website will help “link the work and history of people collaborating and connecting all over the country.”

UChicago scholars have spearheaded the creation of other important video archives, including the South Side Home Movie Project led by Prof. Jacqueline Stewart, which focuses on amateur films and provides a visual history of the neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side.

The archive of the guerilla television movement will cover diverse populations and geographic areas—both urban and rural. Source material will include video interviews with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Studs Terkel about his renowned book, Working; videotapes that document the lives of Black and Latinx youth; recordings of strikes organized by union steelworkers; footage of coal miners in Appalachia; and documentaries about housing, literacy, health care and community issues in New Orleans.

“During the 1960s and 1970s, much of our historical record is in video,” said James Chandler, the William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of English Language and Literature and Cinema and Media Studies. “We will lose this vital history if we don’t save these videos by digitizing the fragile medium and then archiving them and allowing people to access them. You cannot write the history of this time in the U.S. without access to its visual materials.”

The digitization of these fragile videotapes takes time. The project will focus on highly endangered ½” open reel and U-matics, which are first- and second-generation videotapes from the 1970s. Technicians start by inspecting and repairing tapes that have been physically broken. Sometimes they bake the tape to remove moisture. To convert the analog signal to digital files, they must play back and watch the videos in real time.

Once the digitization process is complete, experts at the UChicago Library will review, describe and archive the videotapes and create a website that will contextualize the videos and allow for in-depth searching of the content. To make the collection easily accessible to the public, librarians must create standardized metadata, logging information such as the names of directors and performers, and the location where the tape was recorded.

“This information must be defined in a way that’s searchable and useful to a diverse range of academic researchers and community members,” said Elisabeth Long, associate university librarian for IT and Digital Scholarship at the UChicago Library. “We delve into each video to understand it and how it might relate to other videos in the collection before we can describe what’s really happening using consistent language that allow users to discover connections within the collection. We will also create detailed summaries of what is happening at each point in the video, with links to timestamps in order to help users who may only be interested in seeing one part of the video, not the entire documentary.”

Because the videos touch on such a broad range of topics—including media and cinema, sociology, anthropology and political movements—the digitized collection can also be used to develop undergraduate courses at UChicago in the future. Additionally, public screenings of highlights from the collection will be held.

“This grant represents an opportunity to pull these collections together, to make an archive that allows us both to listen to the stories that were told at the time and to create new ones,” Morgan said.