Make Film History More Inclusive. That's Jacqueline Stewart's Mandate at Academy Museum

The following was published in the Los Angeles Times on September 7, 2021.

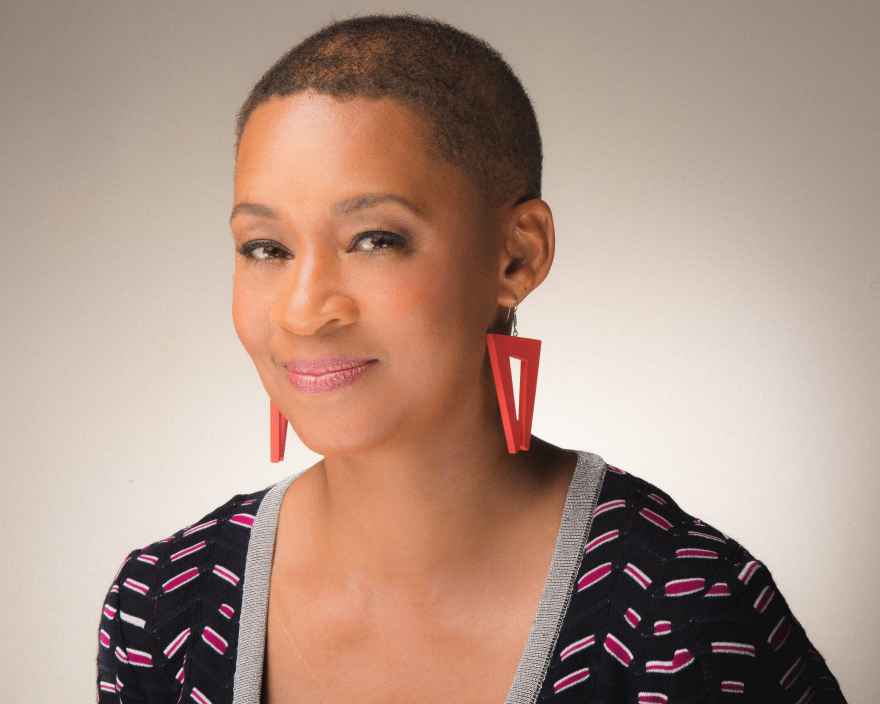

Jacqueline Stewart was already one of the nation’s leading film scholars before she took the job of chief artistic and programming director at the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Now she’s helming the presentation of perhaps the most significant museum dedicated to movies in the country.

While Stewart is on leave from the University of Chicago’s department of cinema and media studies, where she taught American film history, she will continue to appear on Turner Classic Movies, where she was the cable channel’s first Black host. She also participated in TCM’s series “Reframed Classics,” which recontextualized long-beloved movies now seen as problematic by some contemporary audiences, such as “Gone With the Wind” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Stewart co-curated the landmark series “L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema” and co-edited the accompanying book of the same name. She is also currently chair of the National Film Preservation Board, which advises the Library of Congress. In 2020 the Chicago Tribune named Stewart one of its Chicagoans of the Year.

Aside from the exhibitions of objects, from the famous “Rosebud” sled from “Citizen Kane” to the iPhone used to shoot Sean Baker’s “Tangerine,” the Academy Museum is opening two theaters, which will be running movies 365 days a year. Opening with a 70mm screening of Spike Lee’s 1992 “Malcolm X,” the museum also will present “The Wizard of Oz” with live musical accompaniment from the American Youth Symphony.

The first set of programs includes tributes to filmmakers Hayao Miyazaki, Jane Campion, Satyajit Ray and Haile Gerima, with many screenings exhibited on 35mm film prints. And when expected filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Stanley Kubrick are among the initial presentations, it is with unexpected titles such as “The Age of Innocence,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” and “Eyes Wide Shut.”

There will also be talks and other public programs presented by the museum, such as the legacy conversation between actor Laura Dern and her parents, actors Diane Ladd and Bruce Dern.

The Times spoke with Stewart about what made the academy job a perfect fit, how the film programming hopes to win over new fans and her personal favorite among the museum’s many cinematic treasures.

It must’ve been a little bittersweet for you to be named a Chicagoan of the year for 2020 and have that be the year that you’re leaving Chicago.

Jacqueline Stewart: Chicago is my home. I grew up in Chicago, so I didn’t just work there; it’s where I was born and raised. And Chicago has a really vibrant film community as well that’s been expanding and diversifying in some really exciting ways. And I hope that some of the scholarly work and the programming work that I’ve been doing in Chicago contributed to that. But this really struck me as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I think that’s true for the whole team.

Everyone recognizes the specialness of this endeavor and it’s at a scale also that is just unparalleled, we’re narrating all of these different stories about how filmmaking has developed in positive ways, in problematic ways. I was also drawn to this because I don’t have to argue here for inclusive stories of film history. I didn’t come as a corrective to something that wasn’t happening. I came because that was already the baseline philosophy, that we can’t continue to perpetuate the same kinds of hierarchies and exclusions and blind spots in the way that film history is told.

Your title at the museum is chief artistic and programming officer — what does that mean to you?

I would say that I guide the intellectual agenda of the museum, that I am leading our strategy on interacting with the public and that I’m helping the museum think about how all of the different platforms that we represent relate to each other. So the exhibitions are related to our publications, our public programming is deeply, deeply connected to the ways that we engage with multiple constituencies.

And it’s not just the film lovers that we already know — the film buffs — but how can we expand our understanding of who knows a lot about film, who should know a lot about film? So those two elements, the content of our museum — that’s a weird word to use, but really it’s the content of the museum writ large — and the ways that we connect that content to a multiplicity of visitors. And I should say visitors in person and visitors online as well.

Just as it’s taken some time to raise the money and do the renovation on the building, did it take a while for the curatorial focus of the museum to come together? Especially since you were announced for this job a little less than a year ago, what has that process been like?

I really have to give a lot of credit to [museum director] Bill Kramer, because when he came in it was a huge priority for him to ensure that all of the branches of the academy felt that this museum reflected their craft areas. And so a lot of very careful, methodical work happened meeting with branch after branch to talk about: what are the narratives, what are the key objects, what are the priorities that you see in the histories of costume design, hair and makeup design, location managing and so on.

We have a brilliant curatorial team, this amazing group. It’s such a privilege to work with them. And they craft the curatorial vision, but Bill really worked with the curators and the academy branches to ensure that they were in dialogue with each other — so that if a curator was interested in a particular area, there was always somebody that they could consult with who could help to make connections and to continue to advise us on the rotations.

I mean, we’re mounting this huge museum now, but already we’re thinking about what our exhibitions are going to look like a year and a half, two years, five years, 10 years down the line. So that curatorial work is unique for us, I think, because we’re working with so many living filmmakers. And what you see in our core exhibition “Stories of Cinema” — stories, plural, on purpose — is an approach that moves away from a kind of linear walk through film history and instead beautifully crafts a bunch of different kinds of layered narratives.

I feel like that leaves a lot of space for me to cultivate the creativity of our curators and to not feel constricted. But instead to know that there’s always going to be a space for different areas of global cinema, there will always be spaces for silent cinema. And we’re thinking about digital futures. There’s a really capacious and I think dynamic structure that we’ve created here, that I felt like I was able to plug right into. It was sort of like when you teach a film history class, you can teach it in many different ways ... .It’s like a 3-D film history syllabus,

Is the museum presenting the history of cinema or a history of cinema?

There is no the history of cinema. And even if we could claim that there was a history of cinema like you and I are talking now, 10 years from now we would see it totally differently. Not just because there’ll be 10 more years of films that could then influence the way we think about film history, but because old things continue to be discovered.

The Museum of Modern Art found some footage in their own archives a few years ago, featuring Bert Williams, the vaudevillian who wore blackface. We didn’t know that he had done this feature film that had never been completed, but we have these reels of it. And MoMA has these reels and looking at that then rewrites Black film history. So you always have to have that kind of openness.

Those essential film lists are always really interesting to me because what your essential film list was 20 years ago is not what it is right now. And it will change. Hopefully when folks come in, they’ll see things that are familiar to them. They’ll see, Rosebud, for example, they’ll see the ruby red slippers — our “Mona Lisa,” I like to think of those, because people will be lined up to look at those — but the context in which we’re presenting them respects the histories of those objects but then also puts them in dialogue with lots of other objects and films and filmmakers that people have not been familiar with. I’m really proud of that.

Looking at this initial round of public programming, including series on Jane Campion, Hayao Miyazaki, Haile Gerima, Satyajit Ray, Anna May Wong and female film composers, it feels like a very strong statement of intent. What do you hope these programs are saying to potential audiences?

Bernardo Rondeau, who’s our director of film programs, and his team just did an amazing job of conceptualizing the range of programs. I think our opening film programming demonstrates just how broadly we’re thinking about film history. We have our Oscar Sundays, and that will be a perennial presentation, but it’s going to be so meaningful.

I think for us to be able to create these constellations of film histories — and constellations is really the word that I think of here because we have multiple series — it just gets you to look in different directions. And they get you to really explore how different film styles have been developed. It’s always important to do retrospectives of individual filmmakers so that you can see how filmmakers like Campion and Ray and Miyazaki are working in the same medium but in very different modes — it just demonstrates the incredible imaginative possibilities of cinema. And it means something to just put those names together.

I hope that people will come and see something and then stay for another completely different kind of film because they’re here. And so it’s about being inclusive, but it’s also about creating those unexpected connections and about introducing people to things that are in completely different kinds of traditions than they are used to.

You mentioned the ruby slippers from “The Wizard of Oz” as being the “Mona Lisa” of the museum, and I know you must love all your children equally, but do you have a personal favorite object?

No qualms, it’s Evillene’s costume from “The Wiz.” No question. That’s actually a costume that I just think about independently sometimes like, wow, the detail of that dress, the way that Mabel King sort of flounces around in it in that performance. It’s just one of the most striking cinematic objects, I think, ever.

And I have to say when I was talking to Bill Kramer about this role and he was giving me a virtual tour of the museum and he mentioned Evillene’s dress, that totally sealed the deal for me because it’s from a film that I love. And it told me that this museum really was incorporating multiple strands of film history and recognizing artists that had not been recognized with that kind of care before.